|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Opinion

The whole world reports growth in digital subscriptions, minus 1 institution. But this institution dominates the public discourse.

Starter: A look into the crystal ball of future findings

Sometime in the next few weeks The Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) will publish its annual Digital News Report.

Watch out: I predict one data point:

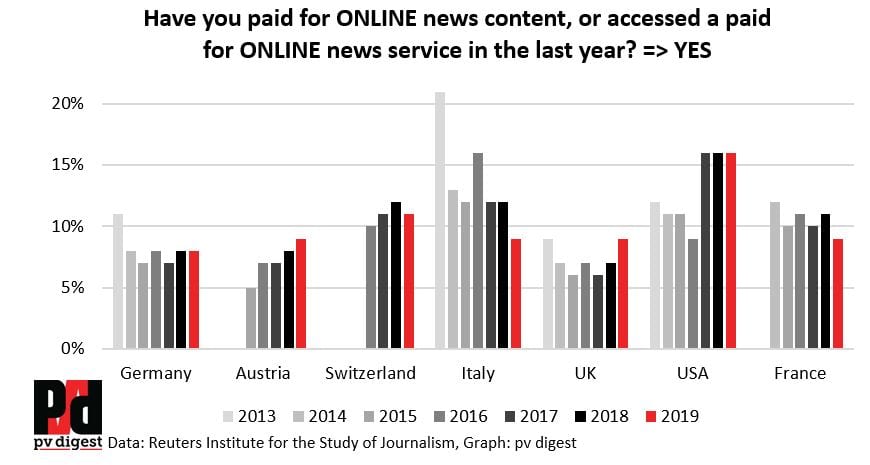

Only around 8% of Germans pay for online news.

How do I know that? Because that’s what RISJ published in 2019, 2018 and 2017. And 2016 and 2015. And 2014.

Yet the whole world of publishing sees growing numbers in the business of selling digital subscriptions

“Impossible,” you might say, “that figure surely must have grown in all those years.” That’s what I will talk about here.

In June 2018, for the first time, FIPP published a ‘Global Digital Subscription Snapshot’. Then, the New York Times had 2,800,000 digital subs, the German newspaper Bild 390,498 and Le Monde in France 160,000. Last year (Nov 2019), these figures stood at 3,800,000 (NYT), 450,000 (Bild) and 200,000 (Le Monde). All in all the FIPP Snapshot in June 2018 showed a list of 9M digital subs. Today it shows nearly 20M digital subs. That is around 100% plus in less than two years.

Other (and more solid) industry research from very different sources, using different methodology, also demonstrate the huge growth in the business of generating digital reader revenues.

PriceWaterhouseCoopers, in its 2019 Global Entertainment & Media Outlook, estimated newspaper digital reader revenue worldwide at 4.2B$ for 2018. A year before, that figure was 4B$. 2018 digital reader revenues for magazines, according to PwC, were 3.9B$, up from 3.4B$ – that’s a plus of 15%.

pv digest annually estimates paid content revenues of newspapers and magazines in Germany. The most current total estimate (published in January 2020) was 527M€. 12 months before it was 396M€. So digital reader revenues in Germany rose by a third in 12 months.

Obviously these percentages are much higher if you look at longer time spans. For example, over the last five years, digital reader revenues at newspapers and magazines worldwide more than doubled, PwC reports. They nearly tripled in Germany, according to pv digest.

That shouldn’t come as a surprise for anybody interested in the media industry. Digital publishing managers from all over the world report a growing business.

Probably even faster than revenues, the number of paywalls is growing. More and more publishers have started offering at least some of their content only to paying users. Paid content or reader revenues have been the dominant monetization strategy for some years now. It is no wonder that a surge in digital subscriptions is reported from nearly every medium worldwide that runs a paywall.

That is, the whole world minus 1 institution

Surprisingly, there is one single institution which claims inconsistent findings. Every year, the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) publishes the results of a huge international survey on the news business, the Digital News Report (DNR). Only one of their many points of observation is the figure of people paying for online news. But probably there is no data point on paid content which is referred to more often anywhere in the world.

Thing is, this data indicates no growth at all in many countries. Though it shows a (plausible) surge of paying readers in the US after the last presidential election, in other countries the DNR even shows declining numbers for some years. Its 2019 edition shows growth in the UK (plausible). But the figure reaches only the same level as in 2013 (highly implausible).

How can this be?

An answer should be that social science and especially surveys pose a lot of methodological problems. Not the least of them being the difference between what a researcher tries to ask for when he is formulating a question and the things happening in the minds of respondents when they read and answer this question.

In the example above, such differences might be found in considerations like these: Are news apps online news? Are ePapers online news? Does ‘paying’ include credit cards being charged recurringly? Will I remember the act of paying in 2019, a year where paying for digital content is a very common behaviour, with the same accuracy as some years ago, when paying for digital content still was an exceptional occurrence? Do people in Italy understand the question (asked in their mother tongue Italian) the same as in Austria (language: German)? You can go on asking such questions endlessly. The researchers at RISJ are fully aware of them.

Unfortunately this particular institution gets the most attention worldwide

And those who are not fully aware of these questions are the public, and especially all the bloggers, trade journalists and experts who take this study as proof that paid content doesn’t work in many countries. Just a short list of articles on the last Digital News Report from publications worldwide:

- Le Monde, France: “The share of people paying for news is stagnating.”

- Niemanlab, USA: “Publishers worldwide are installing paywalls, but many — even most — won’t succeed.”

- Meedia, Germany: “Stagnation on a low level.”

- Press Gazette, UK: “Only 9 per cent of UK survey respondents said they pay for online news.”

- Brasil Online, Brasil: “Majority of people don’t want to pay for news.”

These are just very few examples. But they do give a valid impression of how the Reuters data is understood by the public. In fact, whenever you find a text which says “the number of people paying for news is … (very high in the Nordic countries of Europe, very low in many other countries)” it’s a sure bet that this text refers to the Reuters Digital News Report. And the vast majority of such texts signal: reader revenues are at best a so-so business.

There can be no doubt DNR data is valid in any given market only if it happens accidentally to match the unknown reality. I think that should motivate the people at the Reuters Institute to speak out clearly and publicly that their findings are potentially misleading.

But they don’t. I’ve contacted them several times. They do concede (privately) that their data is ‘irritating’. But instead of thinking about an advisory note, not to speak of re-engineering their whole instrument, they construct theoretical explanations for what might cause their findings which are so implausible at first sight.

Worse, this institution went a step further in dismissing publishers’ success in selling digital subscriptions

In their latest report, they even went one step further in belittling publisher’s success with paid content and digital subs. This is how they express another key finding in their latest report: “The average (median) number of news subscriptions per person among those that pay is one in almost every country.” Read: only one!

Have you noticed this small addendum in brackets: “(median)”? That means that they had to resort to a rather unusual measure to promote the message that the average number of digital subscriptions per person is only 1. They had to use the median instead of the far more popular mean.

If you’d take the mean out of their data, the average number of news subscriptions per person among those that pay is above 1.76 (Not having access to the raw data hinders me from being able to give the real figure. It is possible to deduct this lower bound of the possible range though, which can be computed from the published aggregated data).

1.76 is much nearer to 2 than to 1 subscription, isn’t it? There are good statistical reasons for using the median instead of the mean in many cases. Here, none of those reasons are valid. The only reason to use the median instead of the mean, in this case, is to be able to claim that the number of digital subscriptions per person is as low as 1 and not as high as 2.

So the Reuters Institute, again, publishes a figure which indicates paid content is far less popular amongst users than what most insiders would think, most companies do report, and most sensible reporters would read in the very same data.

It is high time to stand up and ring the bell: The world’s most often quoted study on digital subscriptions is a problem for the industry.

Markus Schöberl, Editor and Publisher, pv digest

About: pv digest is a German-language paid-for trade publication focusing on reader revenue. Its Editor, Markus Schöberl, was a C-suite executive at a national press distribution service provider and a subscription marketing company, both subsidiaries of Axel Springer.