|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The Covid-19 crisis has underlined why it’s crucial for media organisations to have a diverse workforce.

The past year has brought the need for greater diversity and equality in the media industry into sharp focus. The killing of George Floyd and subsequent Black Lives Matter demonstrations, coupled with inequalities exposed by the Covid-19 pandemic, have created a sense of urgency when it comes to levelling the playing field. As publishers restructure and rebuild in a post-Covid world, creating a representative workforce will be more important than ever before.

“Everyone is now faced with a true test to stop the talking and take action when it comes to diversity, equity and inclusion,” says Kerel Cooper, Chief Marketing Officer at marketing platform LiveIntent and co-founder of Minority Report, a podcast that’s leading the diversity debate and features interviews with people of colour, women and members of the LGBTQ+ community in the media industry.

“Based on what happened last year, on what continues to go on and based on the fact that diversity is a very hot topic right now – if a company or an individual can’t make a change or implement some changes in their organisation, they never will. What we saw in the US in 2020 with racial injustice certainly had a major impact on a lot of companies discussing these issues and taking action.”

Cooper and business partner Erik A Requidan, CEO and founder of Media Tradecraft, started Minority Report three years ago after noticing a distinct lack of diversity in their industry.

“Being men of colour in the advertising technology space who went to a lot of events and didn’t see people who look like us, as well as not having someone to look to when we were coming up – we saw that as a gap and wanted to make sure the next generation had content to reference,” explains Cooper.

“They can now see people like themselves in leadership positions telling their stories and learning from them. Minority Report has grown into one of the most diverse catalogues of content across the landscape.”

The scale of the problem

In the UK, the amount of work that still needs to be done to redress the balance in newspapers was illustrated by a study carried out over summer last year by the Women in Journalism campaigning group. Despite the pandemic affecting BAME communities disproportionately – and with the BLM debate raging – the UK’s 11 biggest newspapers failed to feature a single bylined black journalist on their front pages across one week in July.

The study also found that that just six of 174 bylines were for a journalist of BAME background – on the Daily Express, Daily Star, Guardian and Financial Times. Meanwhile, only one in four front-page bylines across the 11 papers went to women, despite the fact a third of UK national newspapers now have female editors.

“As the influence of newspapers wane it is surely more important than ever that papers engage readers,” the chair of Women in Journalism, Eleanor Mills wrote in Press Gazette. “Unfortunately, too many are not moving with the times.

“Given that the most conservative estimates put the non-white population of the UK at 10 per cent it is not surprising that readership of newspapers continues to slump and the audiences they do have skew older and whiter. The press does not reflect the population it is supposed to serve.”

According to Mills some newspapers are taking note with the FT aiming for a gender target of 50 per cent female reporters, editors and experts quoted in stories and 20-22 per cent reporters from the BAME community in the newsroom this year.

Dealing with a backlash

With an estimated 30 per cent of TV reporters in the UK from a BAME background, Mills suggested it was no surprise that a younger, more diverse audience were “voting with their feet”.

Broadcast journalism has benefitted greatly through initiatives like the BBC’s 50:50 Equality Project, which aims to inspire and support the BBC and other media organisations to consistently create journalism and media content that fairly represents gender and diversity.

Speaking at the virtual FIPP World Media Congress 2020, Meera Selva, Director of the Journalist Fellowship Programme at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University, praised the success of the initiative, pointing out how it has created and utilised data to determine how many women are on screen and are being asked for comment or opinion.

Making it onto TV as a reporter is only part of the battle for those who come from BAME communities, with reports circulating that journalists are being racially abused while covering the pandemic.

BBC reporter Sima Kotecha was targeted while doing a live coronavirus report from Leicester in May last year, while Rianna Croxford, the award-winning BBC community affairs correspondent who has covered many Covid stories, including the death of transport worker Belly Mujinga, received racist abuse after being accused by some sectors of the press of biased and agenda-driven journalism.

Croxford remains undeterred despite the attacks. “There’s been such distrust in [certain] communities at how they felt represented in the media, really having people who they feel are objective, impartial and sympathetic has helped in being heard in that way,” she told Press Gazette. “It really taps into an underserved audience or community and can bring a new audience to your platform… and rebuild trust with communities.”

The pitfalls of working from home

While female journalists have done some incredible work during the pandemic, many have found working from home extremely tough, according to Kate McCure, president of the Foreign Press Association.

“Women have taken on a lot more of the burden of homeschooling during lockdown and many have reported that their lives have become immeasurably more difficult,” she says. “Journalism is a very balanced field when it comes to gender but Covid has had an effect on this. A lot of women have had an increased role (at home) that’s been untenable when it comes to the demands of working.

“The pressure is intense because for many of our members the advertising model of their broadcaster or their publication has absolutely dropped through the floor thanks to Covid. At the same time they were expected to work harder than ever on the biggest story of a lifetime. They have just had to cope because they knew their jobs were on the line in a way they weren’t 10 or 15 years ago.”

According to McCure, working from home has increased the chances of severe burnout.

“Journalists more than anyone have adapted really well working from home because journalism is often a solitary thing,” she says. “Where it gets difficult is where there is no separation between your home life and work life. The demands of family falls disproportionately on some people, particularly women of childbearing years.

“And the work pressure is ferocious, knowing that if you don’t keep up you will be replaced by someone half your age and on half your salary. The pressure to compete with people that are younger, cheaper and with fewer commitments like family and mortgages is intense and the burnout rate is high.”

It starts at the top

If media organisations are serious about improving diversity and equality it has to start at the very top, stresses Kerel Cooper, who is the chair of the diversity equity and inclusion executive committee at LiveIntent.

“I don’t think a company will truly change or build on top of their initiatives if they don’t have that strong leadership from the top of the organisation,” he says. “Leaders need to create a runway for employees to do things. At this point diversity, equity and inclusion shouldn’t be this thing that is off in the corner of an organisation, it should be part of the very fabric and that all starts with leadership.”

It’s a sentiment shared by Meera Selva at the The Reuters Institute, where they are also focusing on leadership to ensure greater equality in journalism.

“Ultimately gender representation and diversity is about power,” she told the FIPP World Media Congress. “It’s about seeding power at the top and it’s also crucially about making sure that the people at the top, those making decisions, come from the most diverse range of society. And with gender in particular there is little excuse for it not to be 50 per cent.”

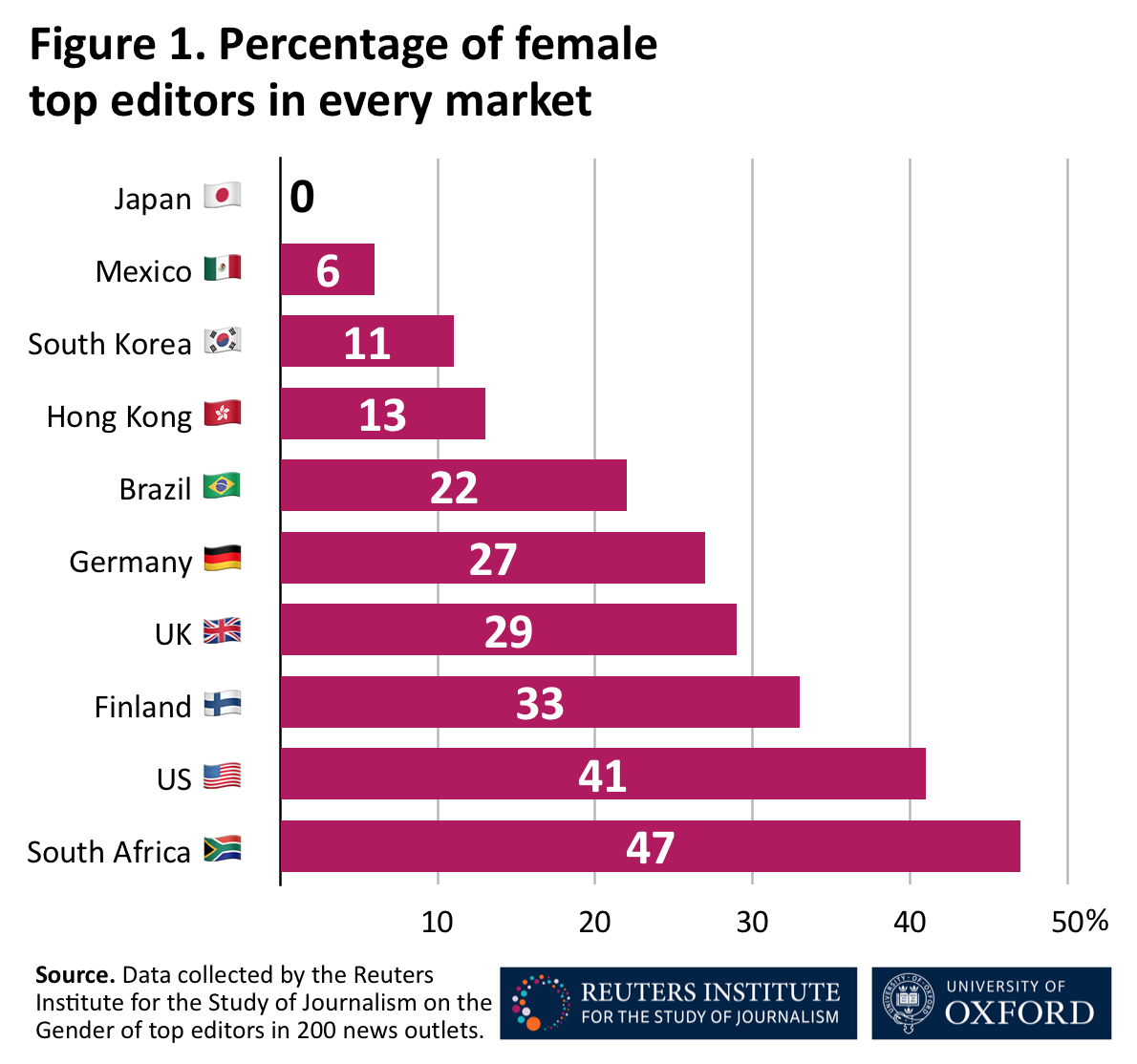

In 2020, The Reuters Institute picked 10 countries from around the world and looked at the 10 online and offline brands in every country to count how many of these brands have female editors.

Statistics from 200 brands across 10 markets showed just 23 per cent of editors were women, despite the fact that 40 per cent of journalists in the 10 countries were female. Japan had no women editors, while South Africa, on the other side of the scale, was best represented with 47 per cent. Percentages for other countries were: Mexico (6 per cent), South Korea (11 per cent), Hong Kong (13 per cent), Brazil (22 per cent), Germany (27 per cent), the UK (29 per cent), Finland (33 per cent) and the US (41 per cent).

“We need to look at what people think leadership looks like, what people think a news editor looks like, what attributes are needed,” added Selva.

“For the news industry to continue to do what it is doing and merely shoehorn women into an existing model would be futile. We need to change. We need to change the way we work, the way we speak to audiences, we need to change the stories we tell as journalists.”

At the BBC, there is a determined effort to make its top structure more representative. Speaking on the The Media Show podcast, June Sarpong, Director of Creative Diversity, said the BBC, like many big media organisations, is diverse at entry level but not diverse enough in terms of mid level and senior leadership.

“In the terms of leadership for BAME the target is 15 per cent and it will take us longer than we would have hoped to reach it,” she said. “But it’s important for so many reasons. If we want to send the right message to the rest of the organisation in terms of talent coming through they need to be able to see examples of progression of people from all backgrounds, because it makes for a better product when you work in a creative industry.”

Getting the job done

As media groups accelerate towards more equality, on-site diversity officers will have an increasingly important role to play. To underline that point, Condé Nast late last year named Yashica Olden as its first-ever global chief diversity and inclusion officer to develop and implement diversity and inclusion strategies.

“As a company, we are committed to recruiting and developing a diverse and inclusive workplace, and as content creators it’s incredibly important that we have a team that has a broad range of perspectives and voices,” Stan Duncan, Chief People Officer of Condé Nast, said in a statement.

Kerel Cooper believes it’s crucial to have a diversity strategist working across departments. “These folks should not just be seen as figureheads but they should actually have real power and authority and real responsibility to impact change.

“But regardless of whether you have a diversity, equity and inclusion officer or not, there’s no one person who’s going to change an organisation or help them push forward – it has to be a collective effort.”

Despite obstacles to making companies more diverse, Cooper is confident a tipping point has been reached.

“I’m cautiously optimistic about the future,” he says. “The events that happened in 2020 aren’t new. In the past it happened, there was a big uproar and then, over time, it died down. We can’t let the momentum die – we have to keep up the education, keep up the initiative and keep putting these injustices front and centre until they don’t happen anymore.

“Sustaining that is very tough – it’s a marathon not a sprint and like with any marathon runner it takes stamina and a mental capacity to keep going over a long period of time. We want to see companies continue to take action not just talk about it.”

Pierre de Villiers