|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

As yet another print magazine shutters to focus on digital, we need to think again about how the magazine of the future will be defined.

The term ‘magazine’ has been problematic for a while now. More and more traditional print magazines are now reducing or stopping print altogether, and are trying to translate their brand to the digital world.

Marie Claire was the latest to announce the closure of their UK print edition last week. The brand will continue to publish online, where they allegedly draw in 2 million monthly readers, according to the Drum. They will also focus investment on their shopping platform, The Marie Claire Edit, which is an affiliate-supported fashion aggregator. TI Media (formerly known as Time Inc) have said that they anticipate this being the title’s biggest source of digital revenue.

The point at which Marie Claire ceases to be primarily a publisher and is instead a retailer is a lengthy discussion for another time. But much of how we perceive brands like this is tied up in legacy perceptions of the title, which will crumble rapidly as the years go on.

Shifting boundaries

To get around defining magazines who no longer have a print aspect, the industry has come up with the handy term ‘magazine media’. This nicely encompasses titles both online and in paper, and means we can talk about Snapchat Stories, YouTube videos and podcasts from publishers all under this one definition.

But there’s a problem here. When a magazine no longer has a print element, what sets it apart from the hundreds of thousands of places that publish content online?

To explore this, let’s go back to the basics of what a magazine is. A magazine, according to many dictionary definitions, is published at regular intervals, is often on a particular subject, and contains a mix of content such as articles and stories. Most are illustrated with photographs or other forms of art.

Some definitions even specify that a magazine is a publication with a paper cover, but using the wider term of ‘magazine media’, we can set aside the paper element for now.

When it comes to translating this online, the ‘published’ part gets tricky. Few publishers push out content in bundled ‘editions’ any more as it just isn’t how content is consumed online. Instead, magazine websites publish articles, videos and other content in the same way as most other websites do; in a continuous stream.

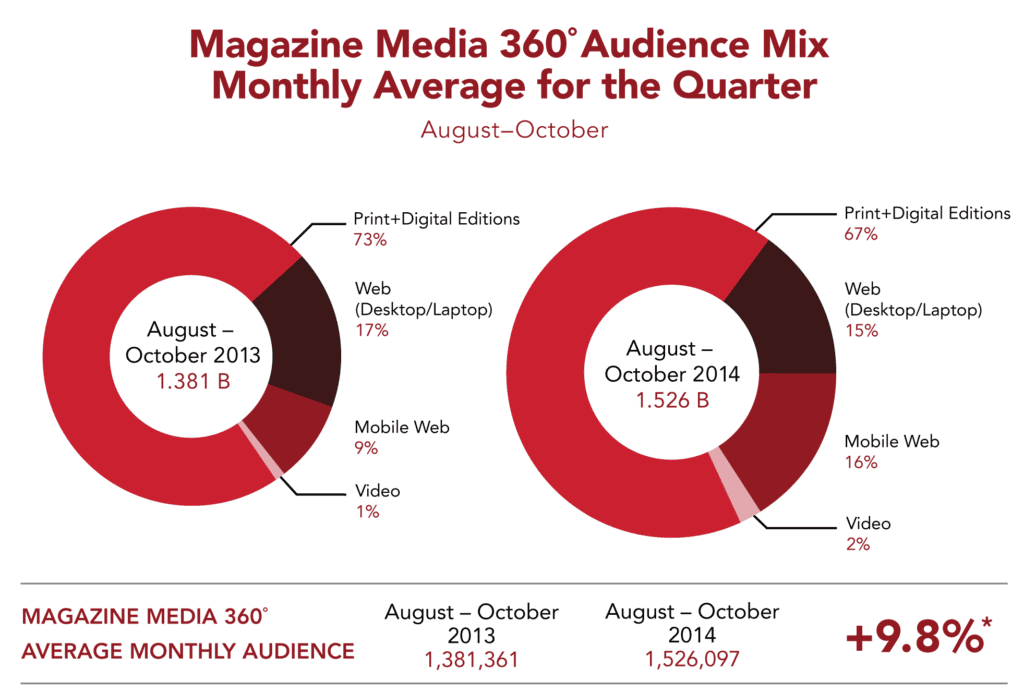

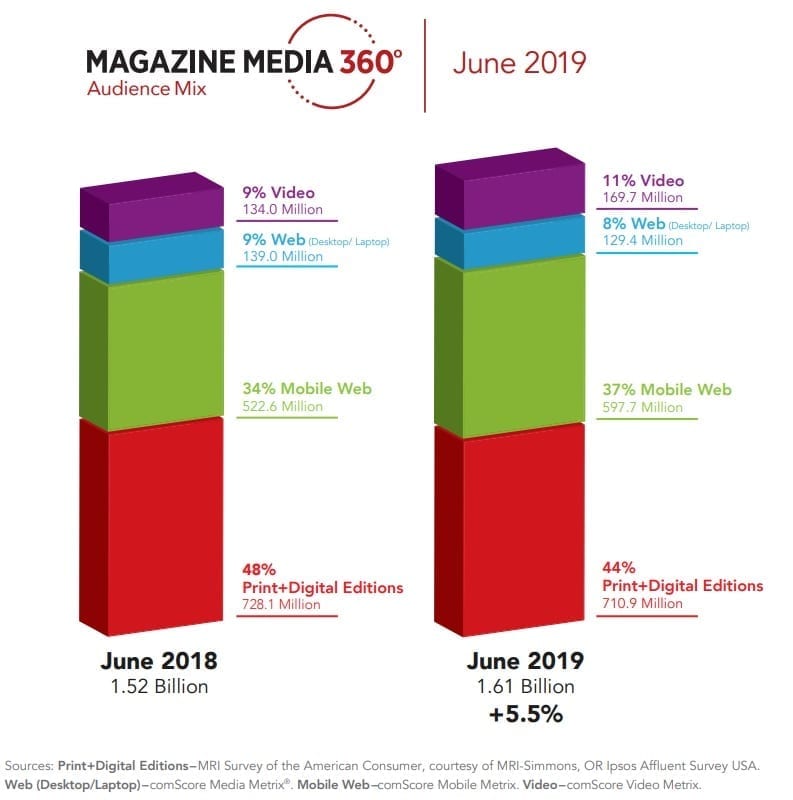

In fact, as of March 2019, 56% of content published by magazine brands is non-edition based, up 6% on 2018. Compare this to 2013 when print and digital editions made up 73% of a magazine brand’s mix, and it shows how quickly publishing habits have changed.

As publishing increasingly moves away from issues, editions and ‘bundled content’, the lines which have defined so many publishing terms over the years are beginning to blur.

Let’s consider two examples here. Glamour, which now publishes just two print magazines a year, has successfully undergone a comprehensive digital transformation to place themselves where their young, beauty-conscious audience lives: on their phones, and on social media.

Now most industry professionals would still call Glamour a magazine, or magazine media. It still publishes every day online, and has a rich usage of other channels like Instagram Stories and Facebook Groups.

But let’s consider Refinery29 alongside it; another women’s media brand. Now R29 is indisputably an online women’s title, but is rarely referred to as a magazine. Yet if you compare what the two do online in terms of publishing content for women throughout the day, there is very little difference.

We can take the magazine terminology to the extreme. Flipboard for example sees magazines as being about editorial curation of content around a certain topic, where users add articles to their own ‘magazines’.

Similarly, Twitter Moments are tweets, videos and images curated by an editor around a particular trend or theme. Would we call Twitter Moments a magazine?

Then there’s all the content in between, which is written, edited and curated by publishing professionals. As another example, Buzzfeed publishes vast amounts of content each day around specified verticals, from cooking to beauty, quizzes and news. Why would we exclude Buzzfeed, or a specific vertical like Tasty from being called ‘magazine media’?

Instagram has been redefining the term ‘magazine’ as well. Earlier this year, the platform launched a series of its own digital ‘Insta-zines’, with ‘editions’ released to help students around exam season with mental health support.

In fact, what’s to stop newsletters being called magazines? Ironically, the timed nature of a curated email drop is closer to the original definition of a ‘periodical’ release of a magazine than many ‘magazine media’ titles publishing content online today.

Perhaps it’s because the term ‘magazine media’ is rooted in print heritage.

That’s problematic. Fast forward a few decades, and few people – certainly not the target audience – will be aware that Marie Claire ever used to have a print title.

Stop and think for a moment about what the next generation will consider a magazine to be. For many of them, they may never pick a physical magazine up. Titles which many of us still associate with a rich print heritage will be fighting to stand out among the nimbler pureplays online.

It’s a trend which has been working up for years; a list of the top global publishers on Facebook is dominated by brands like LadBible, VT and Taste Life.

We either expand our definition of ‘magazine media’ to be more inclusive of publishers without a print legacy, or we risk the term becoming as irrelevant as many of the print copies it once served. Media is evolving all the time, and so should the language we use to describe it.

So how will magazines of the future be defined? When we talk to our children or grandchildren in the years to come about what they think a magazine is, what do we want to hear?

Answers on a (print) postcard, please.